COVID-19 has had widespread impacts on the economy and how we live and work. One outcome of the pandemic has been an accelerated population shift toward the middle of the country, particularly among working-class renters.

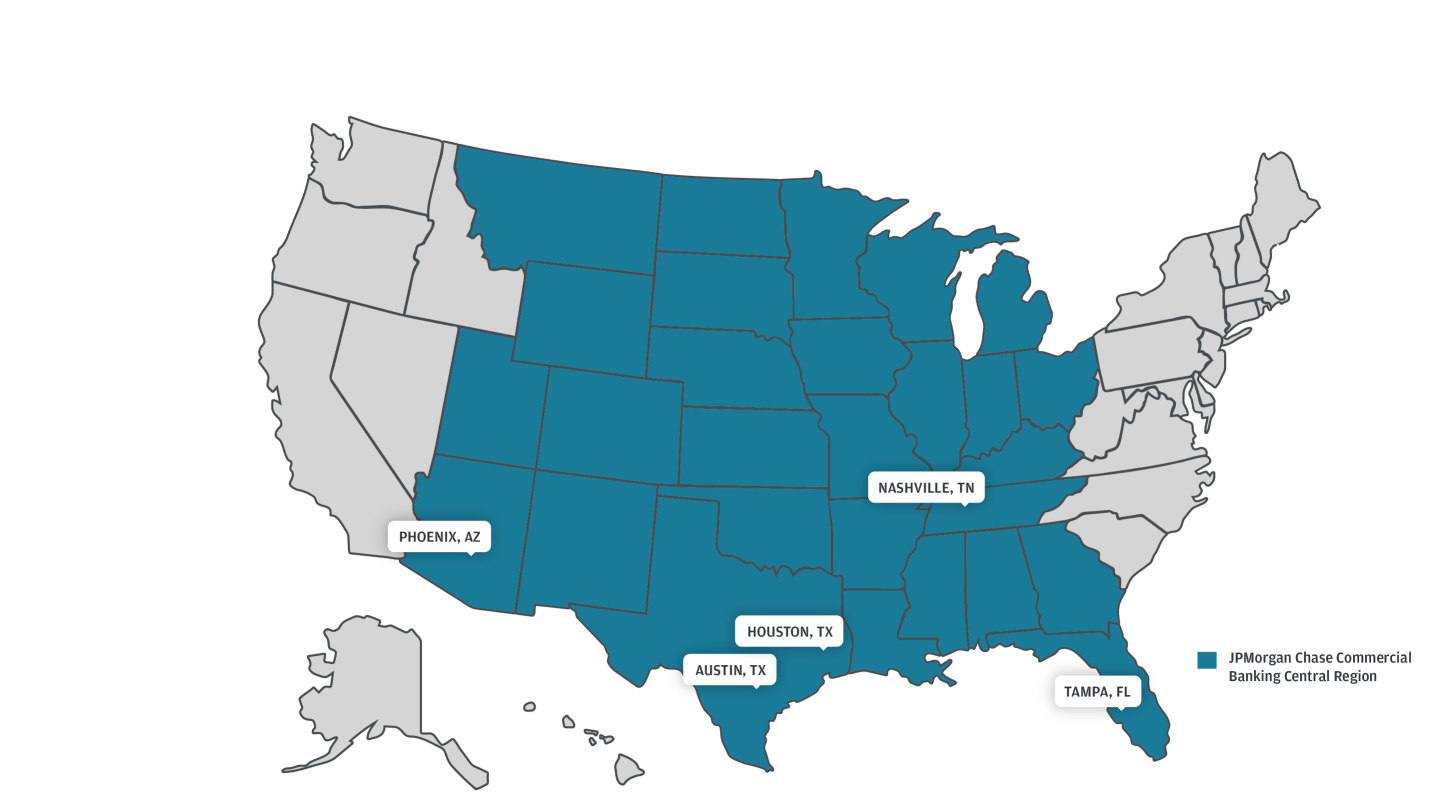

As people leave major metropolitan areas on the coasts for places in the central part of the country—such as Texas, Tennessee, Florida and Arizona—a shortage of available workforce housing can make finding a home difficult. The “missing middle” affects both renters and the cities looking to attract and retain new populations.

Let’s look at domestic migration trends, the current state of affordable housing in the Central U.S. and the outlook for the region in the coming years.

The grass is greener outside large metros

Although a move to the middle was underway before 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the trend.

Analysis from Stephen Whittaker of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland found that domestic migration away from pricey urban areas has been notably higher since the start of the pandemic (Q2 2020 to Q1 2021) compared to recent years (Q2 2017 through Q1 2020).

Migration from high-cost, large metros has increased

9.4%

Toward lower-cost, large metros

13.4%

Toward midsize metros

13.6%

Toward small metros and rural regions

Americans are leaving behind coastal cities and heading for states that provide a high level of opportunity, low cost of living and low taxes. The same Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland data shows:

- 391,720 New York residents moved to regions more than 150 miles away (+14.3% over Q2 2017 to Q1 2020).

- 248,700 residents of Los Angeles have done the same (+7.4%).

Just as New York City and San Francisco saw their highest rate of out-migration in a decade from 2019-2020, Phoenix; Austin, Tex.; Houston; Nashville, Tenn.; and Tampa, Fla. all registered in-migration growth, according to The Brookings Institution.

The conundrum of the ‘Missing Middle’

As the working-class flocks to middle America, an already-limited supply of housing for middle-class renters has proved challenging. Affordable housing exists on a spectrum. The area median income (AMI) of a given city determines what’s considered affordable, and affordable housing is generally available to those who make less than 80% of the AMI.

Often, working families and young professionals, such as mechanics and public employees, don’t qualify for affordable housing because they “make too much” of the local AMI, but they can’t afford market-rate or luxury apartments. Workforce housing is typically for households earning between 80% and 120% of the AMI.

The shortage in available housing for this market can lock out working class renters seeking opportunity in the Central U.S. For example:

- The estimated 2021 fiscal year median family income for the Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, Fla. area is $72,700, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- The 2020 annual mean salary for a postsecondary teacher in the area was $62,500, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Bottom line: A high school teacher in Tampa would make 86% of the local AMI—too much to qualify for affordable housing but likely not enough to afford a market-rate apartment.

This is the “missing middle”: The gap in available housing between luxury, market-rate properties, and affordable lower-income housing facilities, and it’s a vexing problem.

As of 2018, 38.5% of U.S. renters had annual incomes between $30,000 and $75,000, according to a 2020 study from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. That’s equal to as many as 16.8 million Americans who may struggle to find housing that meets their needs and their level of affordability as they migrate toward the central part of the U.S.

Developers, municipalities are eager to build

As it stands, demand for workforce housing in the Central U.S. far outpaces supply.

Fortunately, two forces are working to create more affordable workforce housing in desirable areas close to transportation, healthcare and good schools:

-

Municipalities are increasingly incentivizing construction. Many cities in the region understand the need for middle-income housing and are committing resources to development. This assistance may come in the form of property tax abatements, public funds or disaster relief money. Public participation means rent restrictions and other measures to ensure affordability and availability to working class renters, which developers like.

-

Developers are innovating and using new approaches to building workforce housing. Mixed-income developments—which combine market-rate and middle-class units under the same roof—are becoming more common. There’s no difference in units besides the price of rent, and developers can still use Low Income Housing Tax Credits so long as total rents average out to 60% of the AMI or less.

Also, some affordable housing developers are using modular building as a way to meet demand. The efficient and cost-effective process involves constructing panels off-site and shipping them to the project’s location, where a team assembles to form the structure’s skeleton. For places like Colorado, where weather can be harsh and unpredictable, modular might have the most potential.

Spotlight on Port Arthur Renaissance at Lakeshore

A new mixed-income multifamily development in Port Arthur, Tex., is a great example of public and developer forces coming together to build more affordable and workforce housing.

The Renaissance Apartments at Lakeshore will be a 108-unit project that includes one- and two-bedroom garden-style apartments, as well as two-bedroom townhomes. It will also feature community space, package storage and a play area for kids. Most importantly, even with rents set at 65% of AMI, 70% of units will be affordable and available to those who make up to 80% of AMI. This allows the project to reach a wider share of renters than most affordable developments, said Stephanie Dugan, Senior Director at the National Development Council (NDC), a national nonprofit spearheading the project.

The idea started with the Port Arthur Economic Development Council (PAEDC), which owned the land where the apartments are located. The PAEDC wanted to promote more building of downtown housing and contacted the NDC about applying for disaster relief funds through the Texas General Land Office that could be used to partly finance new construction.

The NDC—which has a long history working with the PAEDC—has also brought in local nonprofit Legacy CDC as codeveloper. This was done as part of the NDC’s mission to build capacity, skills and knowledge with communities and nonprofits it works with. This way, Legacy will have the experience needed to create future multifamily housing projects.

Additionally, JPMorgan Chase has provided bridge construction financing for the project, which is scheduled to be completed fall 2022.

Outlook for Central region workforce housing is promising

Overall, the outlook is positive for workforce housing in the Central U.S. over the next five to 10 years.

- Municipalities and developers are working more closely to identify population needs and increase supply accordingly.

- Attractive destinations for in-migration may continue to grow; Texas and Florida are leading the pack, but places like Kansas City, Mo., and Milwaukee are also popular.

- Demand will likely remain steady. Affordable housing is not prone to the same cycles as market-rate or luxury developments. An economic downturn—however unexpected as the country recovers from COVID-19—may actually create greater demand for affordable workforce housing.

- Changes in federal policy can lead to adjustment periods. So watch changes to tax credits and related programs closely.

We’re proud to align with some of the most passionate developers in the central region, whose mission above all is to build solutions. JPMorgan Chase will continue to commit resources toward facilitating workforce housing development in the Central U.S. and beyond.

Originally published on Multi-Housing News.