While scientists issue dire warnings that climate change is an existential threat to humanity, the markets seem to be largely indifferent to the possibility. Even as the planet warmed over during the last decade, the stock market increased substantially. Credit spreads have reached and remain at historically tight levels.

What explains this seeming disconnect? Not all investors reject climate change science, but markets care about GDP which has not been hurt—yet. However climate change has already had a devastating global impact on biodiversity loss, which falls outside the purview of standard economic accounting metrics.1

That might change, and quickly. We believe that climate change, if unaddressed, is likely to materially impact GDP sooner rather than later.

So, will it remain unaddressed?2 Or will humankind deploy renewables and carbon removal technology to reach “net zero” emissions by the middle of the century?3

The answer here is that significant efforts are likely to be adopted. Yes, to date, people across the world have had trouble coordinating to prevent climate change’s potentially worst outcomes. However, governments are now vowing to meet the challenge, and their responses are likely to accelerate.

Whatever investors may think of climate change, therefore, the savvy should think through the impact that current and likely climate policies will have on markets so they can identify which assets may be hurt and which may benefit. We have some thoughts on both.

The past is highly unlikely to predict the future

Just because adverse weather shocks so far haven’t materially affected global GDP, it doesn’t mean they won’t in future.

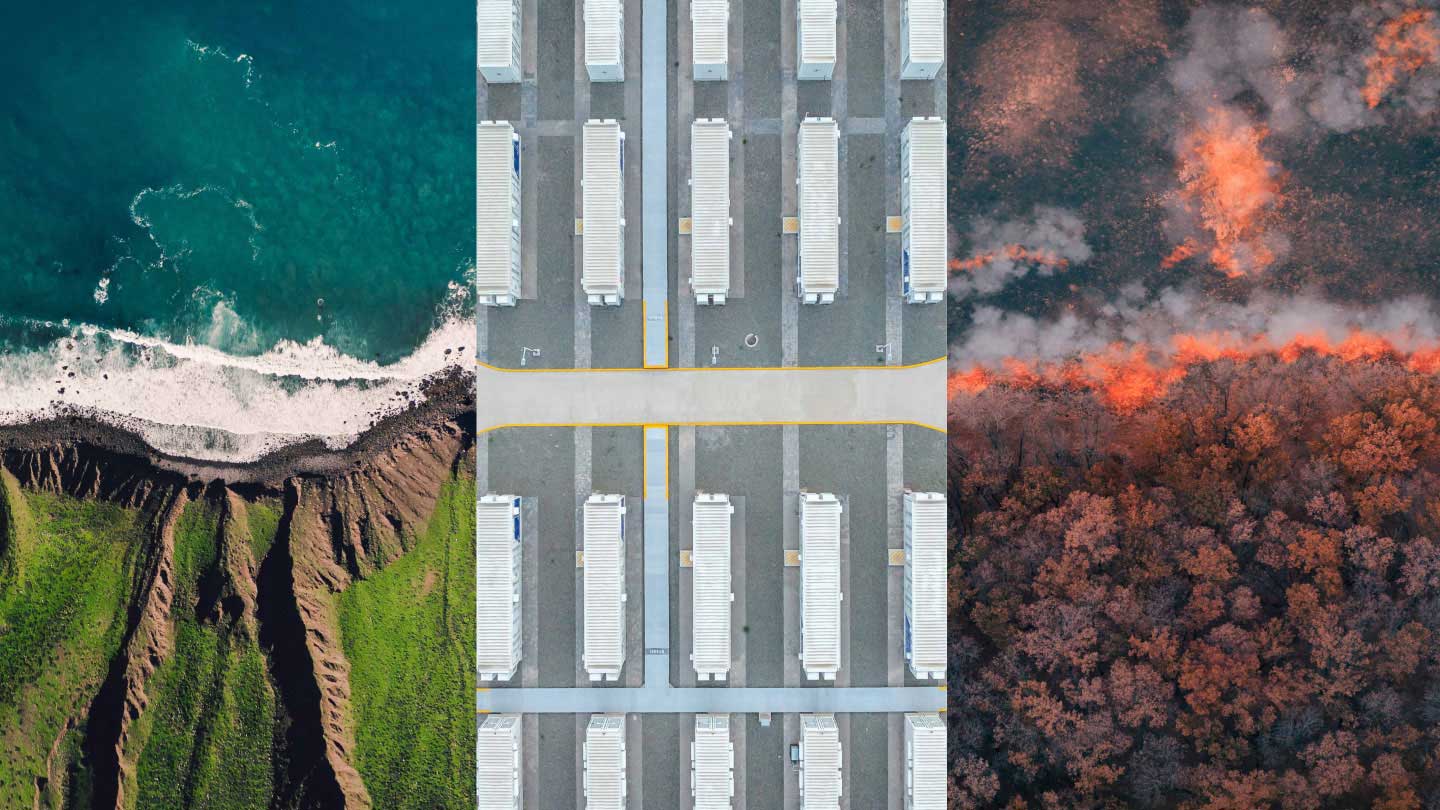

Climate change has picked up pace in recent decades. The increased frequency and intensity of severe weather events.

Historical data that ties climate change to GDP impacts is limited, as the discipline of climate science has only recently begun to be able to attribute individual weather events to climate change.4 But the potential is growing that climate change will have a greater effect on state and/or country GDP. Expectations are that warming will accelerate and increase not only the frequency and severity of events, but also the risk that multiple events will occur simultaneously. Just look at what happened in the United States this August: Hurricane Ida hit Louisiana and flooded the Northeast, while wildfires burned on the West Coast

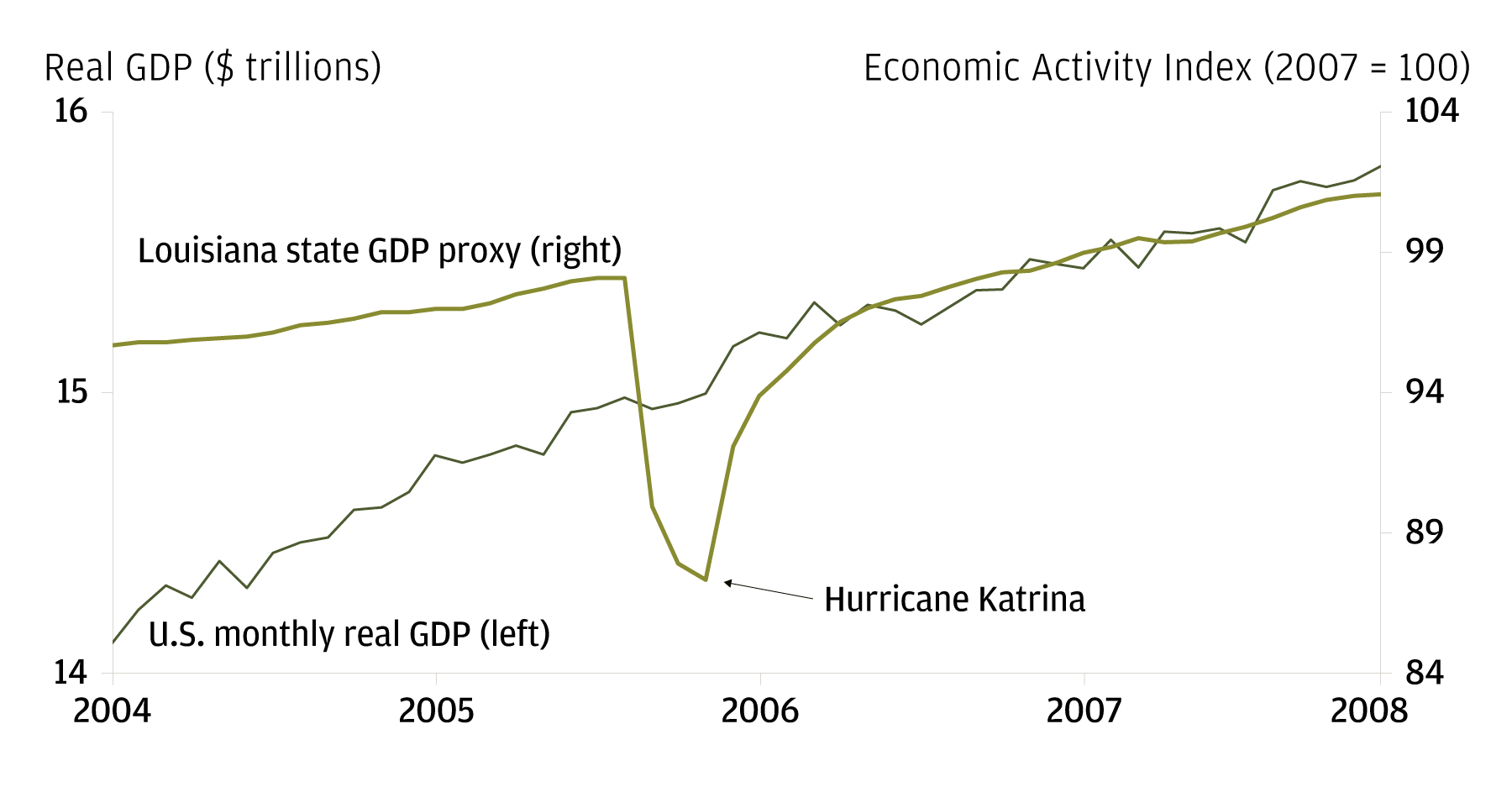

As we write this piece in early September, Ida’s economic damage is still to be tallied. But she did make landfall in Louisiana on the 16-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, which had a significant impact on that state’s GDP even as Katrina’s economic shock went undetected on the national level.

Natural disasters haven't affected U.S. GDP—so far

We would stress that the degree to which a weather event has a more lasting impact on GDP depends on the degree of rebuilding (buildings and infrastructure) done afterward. Katrina didn’t leave a lasting GDP impact, and it’s likely Ida won’t either because a lot of rebuilding will likely be done.

However, at some point, residents may choose to leave an area that is constantly under threat from extreme weather—and that is when more permanent GDP impacts will become a reality.

In addition, more significant damage to global GDP is expected both from potential mass migrations of climate refugees and a variety of potential adverse health consequences related to climate change—including new global pandemics.5 And we all learned in 2020 how damaging global pandemics can be to GDP.

Worse yet, climate change has the potential to sap global GDP growth as we spend more responding to environmental crises.6

Policy to the rescue

While climate change is an emotional and politicized topic, it is at its core a problem of coordination rooted in three challenges:

- Democratic systems—Good at planning for the next roughly 0-10 years, they are generally ineffective at planning for the next and subsequent generations.7

- How we measure GDP—As long as the full environmental damages associated with modern economic activity remain out of sight, they remain out of mind.

- “Path dependence”—Once companies invest in a particular path, they struggle to change direction, and to do so, they often need governments to provide policy incentives and disincentives. The automobile industry’s experience with gas versus electric cars is one case in point.8

Yet responses to potential environmental hazards are possible and happening, largely because governmental bodies are taking the lead.9 In our view, Europe is out in front—providing policy roadmaps that other countries follow.10

This summer, importantly, the European Union made a splash unveiling a new “Fit for 55” package that provides concrete policy prescriptions for cutting emissions by 55% by 2030, so that the region may be on its way to achieving its stated goal: carbon neutrality by 2050.11

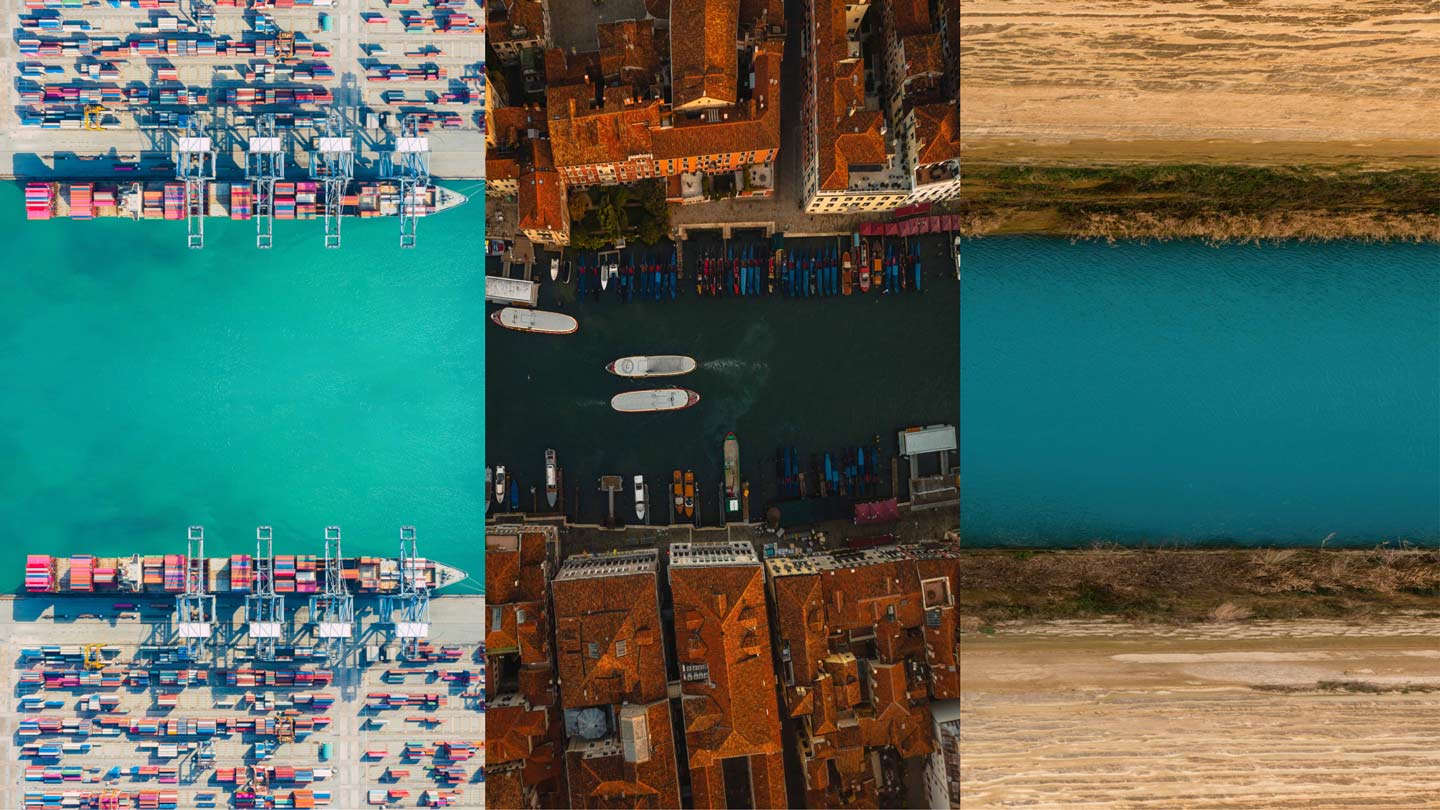

The EU, due to its large domestic market, sets standards for many industries globally, and may force industries across the world to become greener to maintain access to the EU market.

The policy that may have the greatest immediate impact is the EU’s proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which seeks to put a carbon tax on certain carbon-intensive imports (e.g., cement, steel and fertilizers). The explicit purpose of the mechanism is to prevent industries that are fossil fuel intensive from offshoring their operations to avoid EU regulations.

Investors take note

Policy that pushes technological and behavioral change will ultimately filter through to the financial markets. Investors therefore are well advised to look carefully at the potential impact climate policies will have on markets.

Which assets may be hurt?

If regulations keep increasing and consumer behaviors shift in response to fears of climate change, there almost certainly will be more “stranded assets”—that is, assets subject to premature write-downs and operating losses. The coal sector is a prime example. Asset write-downs and declining coal demand have caused the market valuation of assets in the U.S. coal sector to fall from around $35 billion in 2011 to less than $300 million today.

Oil & gas is an obvious candidate for a buildup of stranded assets, as regulations increasingly target the largest sources of greenhouse gas. Multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund have been highlighting the financial risks from low eventual oil & gas prices, which could result in lower cash flows, impairing assets, triggering write-downs and accelerating asset retirements in the sector.12 Oil, gas and related companies already are feeling the pressure, and some are working toward net zero; those that are effective may outperform the sector.

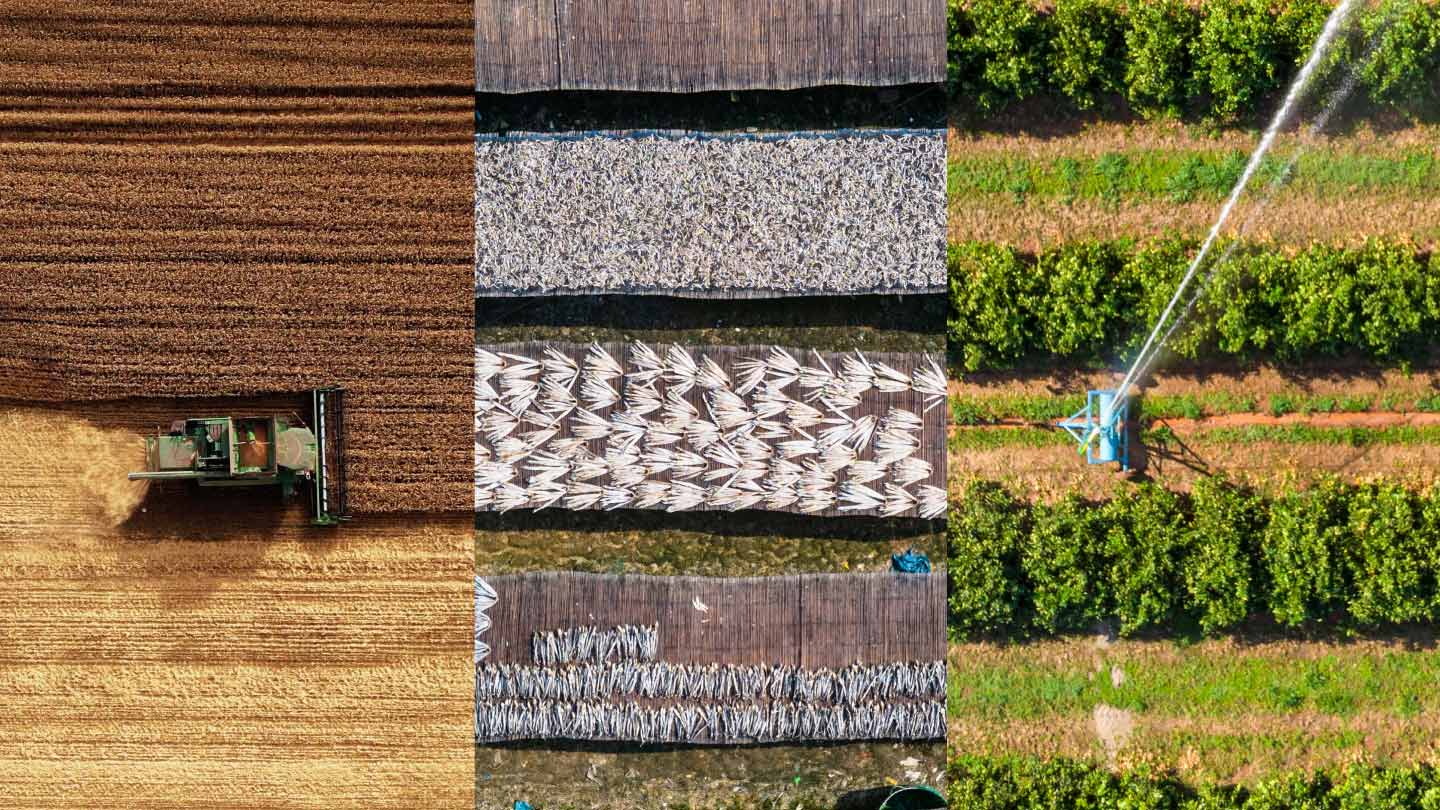

Other sectors are also being systematically targeted for their potential contributions to global warming or environmental degradation, including:

- Commercial agriculture—The sector is responsible for 70% of tropical deforestation (think palm oil planting and cattle grazing).

- Autos—The EU has estimated that up to €240 billion of assets in the European automotive sector are at risk of being stranded due to new technologies such as electric vehicles and ride sharing.13

What assets may benefit?

To organize our search for potential beneficiaries of climate change policies, we look at three broad categories:

- Technologies that already are cost-competitive compared to fossil fuels. Such technologies are now hitting exponential adoption curves globally. Great examples include solar, wind and electric vehicles. While there is likely still a potential of gains for investors who put their money to work in these sectors, particularly in areas that support these technologies (think energy storage and semiconductors), markets are already reflecting expectations of significant adoption over the next 10 years. This means many of the outsized gains for investors in these sectors are likely behind us..

- Technologies that exist but are not yet cost-competitive compared to fossil fuels. In a net-zero emissions world, how will we move around large vehicles (commercial airplanes and cargo ships)? The answer will likely be found in hydrogen and bio-based fuels. In this second category, where investors may enjoy above-average returns over the next decade, we would also place natural carbon-capture technologies, such as forests and kelp farms.

- “Sci-fi” technologies that don’t exist yet or are currently wildly inefficient from a cost-to-reward perspective. Some speculative technologies may take decades to pay off, and offer lottery-ticket-type returns. Current examples: carbon-capture machines to be used for cement and steel production, mechanical removal of carbon from the atmosphere or ocean, next-generation nuclear fission power plants, and the holy grail of harnessing the power of nuclear fusion in a cost-effective way.

We can help

We do expect climate change to increasingly impact GDP. Technological breakthroughs will be key to address the challenge—and many of these ideas make interesting investments. Speak with your J.P. Morgan team to see what type of climate-related investments might suit your financial goals now—and for our foreseeable future.

References

According to one estimate, in the last 60 years there has been a 70% decline in the population of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians. WWF Living Planet Report 2020.

Scientists generally agree that if climate change is left to continue on its current trajectory, the world will be 4⁰C warmer by the latter part of the century and the World Bank says that a four-degree-warmer world would see “unprecedented heatwaves, severe drought and major floods in many regions.” Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research & Climate Analytics, “4⁰ Turn Down the Heat: Why a 4⁰ Warmer World Must be Avoided” World Bank, November 2012 https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/sites/ppp.worldbank.org/files/documents/WorldBank_turn%20down%20the%20heat.pdf

“Net zero” refers to a state in which the greenhouse gases going into the atmosphere are balanced by removal out of the atmosphere. IPCC, “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis.” August 2021 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

IPCC, “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis.” August 2021 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

World Health Organization, February 2018 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

It is for this reason that some have labeled climate change as a new “Malthusian trap” for the global economy, taking a page from history when at the end of the 1700s the British economist Thomas Malthus recognized that there were inherent limitations to GDP growth because population growth was consistently exceeding the growth of the food supply.

Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney in 2015 coined the term “the tragedy of the horizon,” to explain how the catastrophic impact of climate change will impose a cost on future generations that the current generation has no incentive to fix.

Philippe Aghion, Antoine Dechezlepretre, David Hemous, Ralf Martin, John Van Reenen“Carbon taxes, path dependency, and directed technical change: evidence from the auto industry,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 124, no. 1, February 2016

An example of global environmental coordination: The 1987 Montreal Protocol, which began a process of phasing out the production and use of ozone-depleting substances such as chlorofluorocarbons in aerosol spray cans. The impact has been a significant reduction in global ozone-depleting substance emissions, and an improvement in the health of the planet’s ozone.

European Commission https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en.

The long list of proposed policies contains regulatory carrots and sticks, including, for example, banning new fossil fuel cars by 2035 and expanding the list of industries in Europe’s Emissions Trading System that puts a price on emissions. For a full list of proposals and accompanying details see: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en

IMF, “No Time to Waste,” September 2021 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/09/pdf/fd0921.pdf

Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney