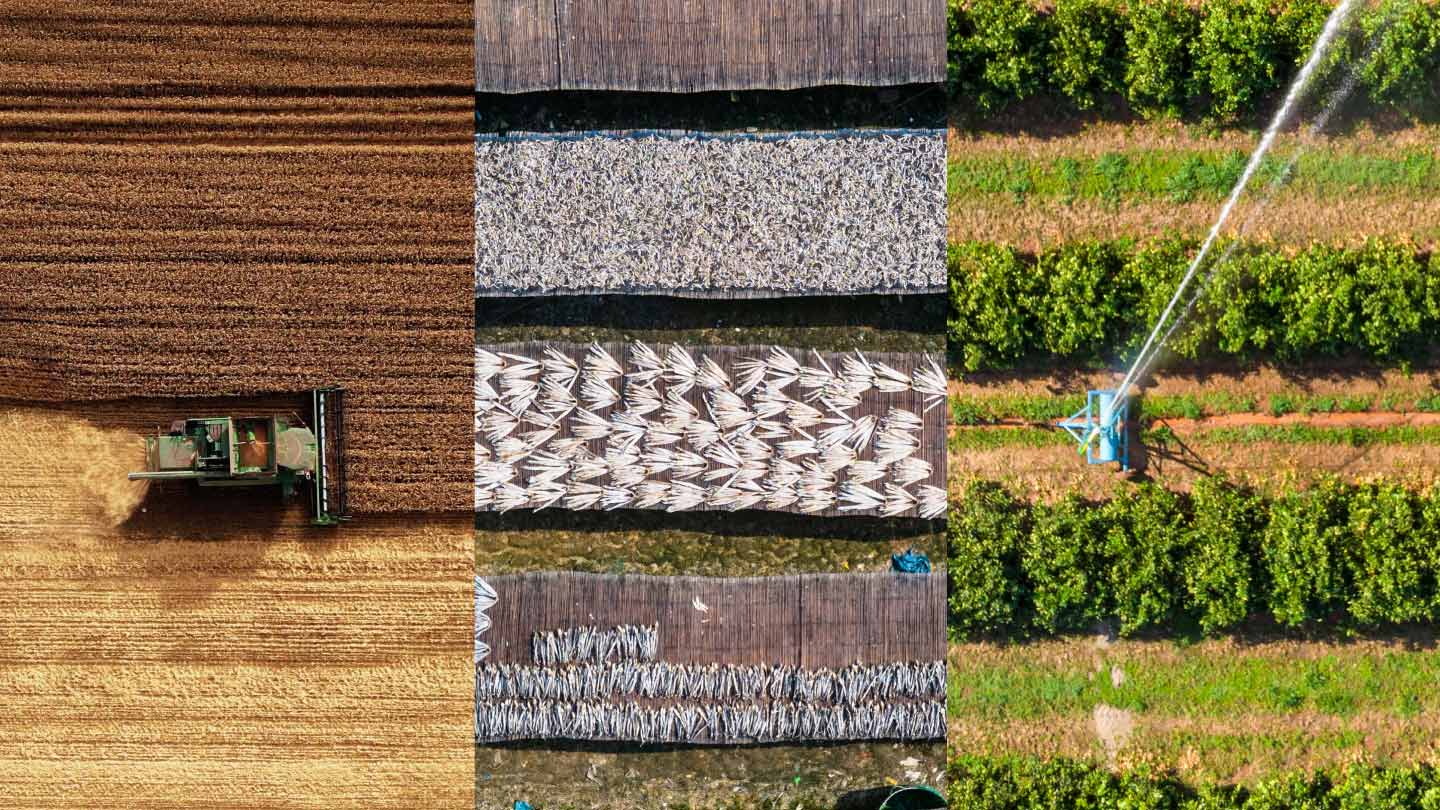

The shifting winds of farming and trade — and what it means for the future

Dr. Sarah Kapnick breaks down the global state of agriculture and trade, the risks inherent in current practices and the strategies countries and corporates are exploring to manage risk and build toward food security.

Agriculture has been impacted by a changing climate at every stage, from farming and distribution to risk management and commodity pricing. Degrading soil health and water supply are weakening the foundations needed to farm and trade food. Vulnerabilities like market concentration and trade tensions pose threats to the global supply chain.

To pursue a food-stable future, business leaders and governments alike should consider investing in innovative solutions and risk management strategies including regenerative farming and supply chain diversification.

In “The Fate of Food in a Warming World,” Dr. Sarah Kapnick dives into the current state of global agriculture, stressors of production from environmental threats and the impact of changing trade dynamics.

“Investors and business leaders must recognize that environmental threats and shifting trade dynamics are fundamentally changing the risk landscape for agriculture commodities. Relying on historical patterns is no longer sufficient for decision-making.”

Dr. Sarah Kapnick

Global Head of Climate Advisory, J.P. Morgan

About Dr. Sarah Kapnick

Dr. Sarah B. Kapnick is the global head of Climate Advisory at J.P. Morgan. In this role, she advises the bank’s clients on climate, energy, biodiversity and sustainability topics. Responsible for overseeing the firm’s climate thought leadership strategy, Dr. Kapnick leverages extensive technical and scientific expertise to drive content strategy and advise clients at the intersection of finance, climate science, commerce and national security. She has received several recognitions for her work at J.P. Morgan and Climate Intuition series, including being named to the 2025 TIME100 Climate and Bloomberg Green “Ones to Watch” lists.

She was previously with the bank’s Asset and Wealth Management division as senior climate scientist and sustainability strategist.

Prior to her current role, Dr. Kapnick was chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), responsible for guiding the programmatic focus of NOAA’s science and technology priorities. She spent a decade at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) leading research on seasonal climate prediction, mountain snowpack, extreme storms, water security, climate economics and climate impacts.

Dr. Kapnick earned a PhD in atmospheric and oceanic sciences with a certificate in Leaders in Sustainability from UCLA and an AB in mathematics with a certificate in finance from Princeton University.

Subscribe to the Climate Intuition series for the latest insights on how climate change impacts strategic decision-making.

Related insights

No results found

Adjust your filter selections to find what you’re looking for