From: Research Recap

Every two weeks, each new podcast episode will bring you the latest news and views from J.P. Morgan’s award-winning Research analysts, who cover everything from sector-specific trends to the state of the global economy.

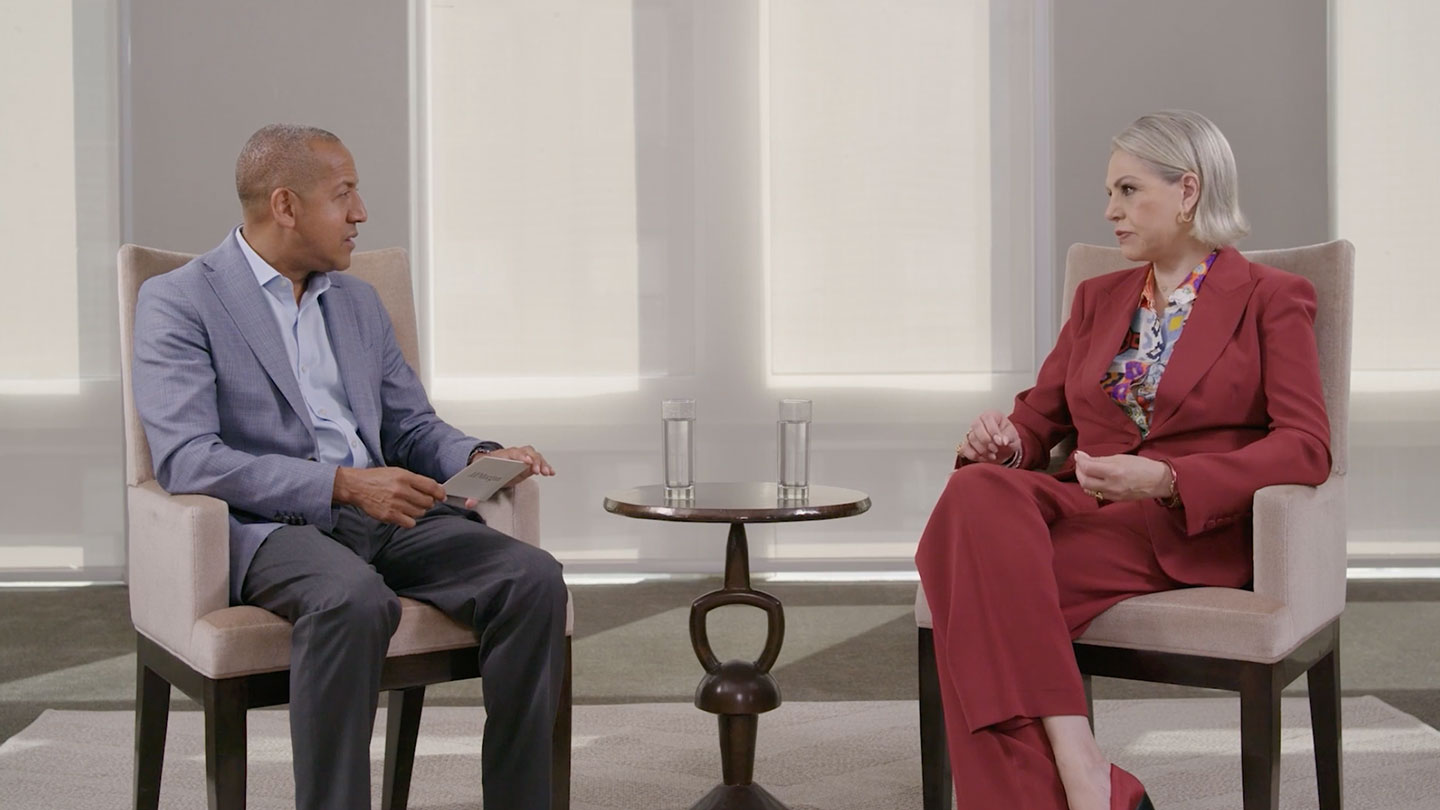

Join host Phoebe White (Head of U.S. Inflation Strategy) as she chats with Michael Feroli (Chief U.S. Economist) and Jay Barry (Co-Head of U.S. Rates Strategy). Together, they tackle the hard-hitting questions: Why is the U.S. economy not slowing down? Is a “soft landing” scenario a given? And how will all this translate across to the U.S. rates markets?

What will the Fed do next and does J.P. Morgan forecast a soft landing?

“In our forecast, we have some modest rate cuts in, beginning in the third quarter of next year … I could see a scenario where the Fed is on hold at these rates for all of next year. Certainly that wouldn't be unprecedented.”

Michael Feroli

Chief U.S. economist, J.P. Morgan

J.P. Morgan’s Chief U.S. Economist Michael Feroli forecasts a scenario with some modest rate cuts in the third quarter of 2024, which could lead to a soft landing. However, Feroli also acknowledges that forecasts do not always pan out as expected.

Will inflation keep coming down?

“Inflation will not get back to a completely comfortable place. But we do think that this disinflation has further to run.”

Michael Feroli

Chief U.S. economist, J.P. Morgan

“We have had disinflation occur alongside resilient growth,” Feroli said. I think some of that is the dreaded transitory story actually having some validity to it, which is to say, particularly in goods inflation, a lot of the things that really pushed up inflation were related to supply disruptions that have mostly ameliorated themselves.” Feroli expects fourth-quarter Core CPI (on a quarter-over-quarter basis) to be at 4%. Next year, it should come down further to 2.7%.

How are economic dynamics translating across to the rates market?

“We have 10-year yields down from their peak at the time of this recording, sitting near 470. But that’s still up, close to 90 basis points in the last few months.”

Phoebe White

Head of U.S. Inflation Strategy, J.P. Morgan

Part of the move to higher yields can be attributed to greater economic resilience and higher-for-longer interest rates. But since September, drivers of change have been relatively stable. “Forward inflation expectations have risen modestly. And that can explain some of the move here,” said Jay Barry, Co-Head of U.S. Rates Strategy at J.P. Morgan. “But in aggregate, we look at the moves over the last month or so … We can only explain about 50% of that move … It means that long-term treasury yields are now more dislocated from these fundamental drivers than they’ve been at any point over the last year.”

Where are yields headed from here?

“When we put the pieces of the puzzle together, it makes us think that over the medium term, long-term rates … are going to remain more anchored at higher levels for longer periods of time.”

Jay Barry

Head of Global Rates Strategy, J.P. Morgan

The Treasury is in the early stages of increasing long-term coupon auction sizes. “We think this means that Treasury duration supply is going to increase by about 30% between 2023 and 2024,” Barry said. He predicts that in the medium term, long-term rates will stay higher for longer. “We think it translates into steeper yield curves over time,” he added.

Tune in to more episodes of Research Recap on Making Sense, the home of J.P. Morgan podcasts. Research Recap delivers the latest news and views from J.P. Morgan’s award-winning analysts, covering everything from sector-specific trends to the overall state of the global economy.

This communication is provided for information purposes only. Please read J.P. Morgan research reports related to its contents for more information, including important disclosures. JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively, J.P. Morgan) normally make a market and trade as principal in securities, other financial products and other asset classes that may be discussed in this communication.

This communication has been prepared based upon information, including market prices, data and other information, from sources believed to be reliable, but J.P. Morgan does not warrant its completeness or accuracy except with respect to any disclosures relative to J.P. Morgan and/or its affiliates and an analyst's involvement with any company (or security, other financial product or other asset class) that may be the subject of this communication. Any opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This communication is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. J.P. Morgan Research does not provide individually tailored investment advice. Any opinions and recommendations herein do not take into account individual client circumstances, objectives, or needs and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. You must make your own independent decisions regarding any securities, financial instruments or strategies mentioned or related to the information herein. Periodic updates may be provided on companies, issuers or industries based on specific developments or announcements, market conditions or any other publicly available information. However, J.P. Morgan may be restricted from updating information contained in this communication for regulatory or other reasons. Clients should contact analysts and execute transactions through a J.P. Morgan subsidiary or affiliate in their home jurisdiction unless governing law permits otherwise.

This communication may not be redistributed or retransmitted, in whole or in part, or in any form or manner, without the express written consent of J.P. Morgan. Any unauthorized use or disclosure is prohibited. Receipt and review of this information constitutes your agreement not to redistribute or retransmit the contents and information contained in this communication without first obtaining express permission from an authorized officer of J.P. Morgan.

Copyright 2023 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved.